Thomas London: Art with Tea

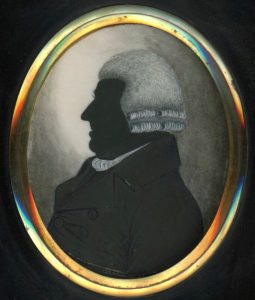

Thomas London’s silhouettes are stylistically distinctive: neatly painted on an ivory base in shades of grey watercolour with Chinese white highlights, the profiles are always beautifully detailed and are typically set against a lightly hatched background. He was painting around the turn of the 19th century, his latest known profile is dated 1817, a period of elegance and streamlined fashion that lent itself well to the profilist’s artform.

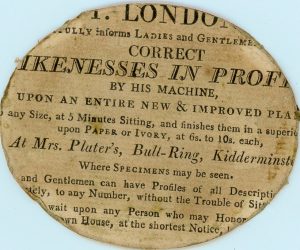

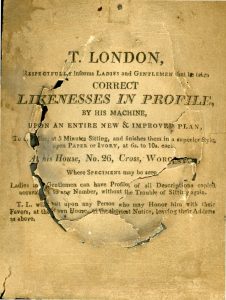

London used two trade labels: his earliest pieces were painted whilst in Kidderminster –

his later pieces at 26 Cross, Worcester –

Personal Life

Research has revealed that Thomas London was born in 1780/1, most likely in Worcester. His parents or siblings have not been traced. On 12 July 1803 at St Nicholas’s Worcester, Thomas married Frances (Fanny) Yarnoll (1776-1868), the daughter of a local shoemaker; it was a double ceremony shared with her sister Sarah. Thomas and Fanny had at least six children though four died young including a boy who died a couple months prior to their wedding.

Career

Despite having his own printed trade labels, Thomas London was not a prolific artist. While most silhouettists advertised a sitting time of just one or two minutes, London asked for five minutes. His work was painstaking with particular attention being paid to the costume details including the delicate fabric patterns.

Men were probably quicker for him to paint though he still took care to render the texture of the wigs to good effect.

Each silhouette must have taken many hours or even days to complete yet the cost to the sitter was no more than ten shillings, equating to about £40 in today’s money. That was clearly not a great living for a man with a young family. No advertisements have been traced for London’s silhouette business so sitters may also have been thin on the ground.

Removal to Bath

At some point between 1818 and 1824, the London family upped sticks and moved south to Bath. Why they made the move is unclear: perhaps Thomas hoped to attract a better clientele for his art, though there is no record that he painted profiles whilst there; perhaps he was seeking the health benefits of the spa waters; or perhaps a new and more lucrative business opportunity had presented itself.

His new career was actually as a tea merchant. The Worcestershire General and Commercial Directory (1820) lists a Thomas Harris, agent to the East India Tea Company living at what was London’s address, 26 Cross in Worcester. It seems likely that Harris not only inspired this new venture but that he also managed the supply of tea direct from the East India warehouses to Thomas London’s own warehouse at No. 3 Walks, as advertised by London in the Bath Chronicle (February-March 1824).

No. 3 Walks was a central location situated opposite the newly opened Literary Institute. It was to remain their abode for the next two to three decades.

Fancy Cabinet Painting

For a man of Thomas London’s artistic talents, tea dealing must have seemed rather dull so that might explain why he now turned his hand to painting furniture and small boxes such as tea caddies and jewellery cases. London used one of his tea adverts in the Bath Chronicle to invite the public to view a ‘magnificent cabinet of Chinese characters’, the admission charge being one shilling for two people. It must surely have been a masterful piece to justify an admission charge. Years later in 1837, long after Thomas London’s death, his widow was to advertise this cabinet for sale along with a second one. She valued them at a princely £300 each though was prepared to accept less! Fanny London and her son were still very much in business during the 1830s continuing to produce fancy cabinets to order − Thomas junior, having inherited his father’s artistic skills. Thomas was also offering instruction in the Chinese style of painting, presumably to include the fashionable art of japanning. His sister Elizabeth meanwhile had taken up miniature painting and so she too would have helped with the ongoing business.

His Legacy

The Bath Chronicle announced the death of Thomas London on 5 September 1826 at the age of 45. His widow was to outlive him by 42 years passing away at her son’s house in 1868 at the age of 93. The couple were reunited in the Argyll Chapel burying ground at Bathampton, Bath.

It is though Thomas London’s attractive and distinctive silhouette work that remains his enduring legacy.

© Wigs on the Green

Research assistance by B. Wellings