William Hamlet the Elder

The chance discovery of an article published in the first Afro-American newspaper Freedom’s Journal (28 March 1829) has prompted new research into William Hamlet’s background and family. The article concerned the arrest in Norfolk, Virginia of William Hamlet’s third son, George. George was living in New York but, whilst travelling, he was ‘arrested and cast into a loathsome prison’ as he did not have the necessary documents to prove that he was a free man. The article goes on to state that ‘the father of the individual … is Mr. William HAMLET, of London, a man of colour, who is profile painter to his Britannic Majesty and the Royal family, and his mother, is a white subject of the same government: so that if the “righteous judges” of Norfolk, are desirous of seeing the body of George HAMLET sold to the highest bidder in the market place of the aforesaid republican city they will find themselves most sadly mistaken’.

An advertisement in Jackson’s Oxford Journal in 1785 stated that William Hamlet was ‘From Abroad’. His birthplace remains a mystery but the Bath Abbey Register has revealed that ‘William Hamlet a Negro’ was baptized on 11 November 1772. His parents are not recorded nor did he have a sponsor. He would by then have been in his early twenties; several similar baptisms are recorded around that time. Perhaps William arrived on these shores from somewhere like Bermuda after serving time in the Royal Navy.

The next official record for Hamlet is his marriage on 17 April 1779 at St Thomas’s Salisbury to eighteen year old Elizabeth Morgan (bapt. 1761). Elizabeth was illiterate so the register was signed with her mark. Presumably Hamlet had in the interim moved from Bath to Salisbury.

Just over eight months later on 21 December 1780 their first child, William, was baptised in the same church. They went on to have four more children: Thomas (baptised 29 October 1783), Elizabeth and George, presumably twins (baptised 31 August 1788) and Charles (baptised 27 December 1792).

The earliest recorded silhouette by Hamlet is dated 1785 and depicts an Oxford scholar. The first known reference to him as an artist is an advertisement in Jackson’s Oxford Journal midway through 1785. By then he was married with two children.

From the advert it appears that Hamlet was now using two new devices: a hard to envisage ‘methodical Model of Amusement’ small enough to fit into a pocket book and designed to take two quick likenesses; and, a ‘Profile Reflector’, a larger mechanical device using mirrors that Hamlet had launched in Bath where he took 400 drawings. A few months later the device was on show in Birmingham by which time it had clocked up 1,000 drawings. Presumably he and his device continued to tour during the following few years.

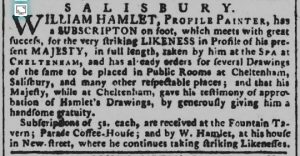

1788 was a propitious year for Hamlet as not only did he become a father again (to twins) but he was also granted a sitting at Cheltenham Spa by King George III. This was for a full-length profile of which copies were subsequently painted to order. The King was clearly pleased with his portrait as he paid Hamlet generously for it and then went on to grant him further commissions of himself and his family over the following two decades. Hamlet was quick to capitalise on the royal patronage in advertisements placed in the Salisbury and Winchester Journal in the autumn of 1788.

The following year found Hamlet working in Oxford. He advertised in the Oxford Journal (21 November 1789) using the strapline ‘Encouraged by their Majesties’. It is interesting that he was still only charging 2s. 6d. for a basic silhouette on card and 10s. 6d. for a full-length silhouette on glass.

HRH Princess Mary. Private Collection

Apart from the birth in Salisbury of his youngest child in 1792, William Hamlet effectively disappears from public life during the 1790s. There are no known examples of silhouettes from this period and no advertisements have been traced. Did he take up a more regular position in order to support his growing family? Might he have focused on teaching drawing? Maybe he travelled abroad?

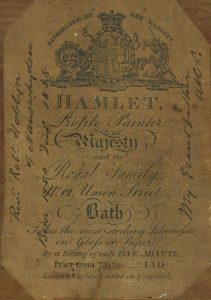

At some point the family moved from Salisbury to Bath. Hamlet’s eldest son, also named William, was married at St Michael’s Church in Bath on 10 August 1801. (The Abbey Church was being repaired at this time.) William Jnr’s wife, Jane Fox, came from Salisbury: presumably the couple had met and courted there before the family’s removal to Bath? Like her mother-in-law, Jane was illiterate. It was in Bath that Hamlet’s career as a silhouettist revived. Indeed the majority of surviving silhouettes by Hamlet were painted during the period 1805 to 1816.

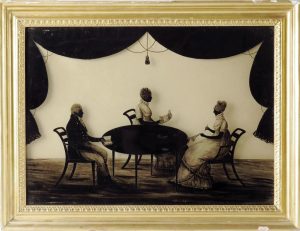

During these years Bath was at the height of its popularity with a steady influx of well-heeled visitors arriving to take the waters, and all seeking diversions to while away their days. Capitalising on this, Hamlet ran a busy studio in Union Street, within easy walking distance of the Roman Baths and the Abbey.

This coincided with the new streamlined female fashion of high-waisted dresses and dainty slippers that lent themselves to elegant silhouettes.

William Hamlet Jnr, who had joined his father in the business, died in 1815 whilst in his mid-thirties. His widow (possibly still illiterate) was left with five children aged between 2 and 13 years of age with a sixth child born three months later. Presumably her father-in-law would have done his best to support the young family but it was around this time that Hamlet Snr’s career as an artist ceased perhaps brought about his advancing years and possible infirmity, but undoubtedly affected also by his grief at losing his eldest child.

William Hamlet died in 1822, seven years after the death of his son, and was buried on 19 September. If his recorded age of 73 on the burial record was correct, it would place his birth in 1748 or 1749. He was living at No. 79 Avon Street, an area of Bath that was filled with boarding houses during the 1800s and was described as ‘a desperate and impoverished place’. Church burial records stand as mute testimony not only to its multiple occupancy but to its being disease-ridden with consistently high death rates.

This was a sad and lowly end to a career that had peaked with Royal patronage but which was clearly driven by hard work and a talent that manifested itself in precise and neat work coupled with an eye for detail.

© Wigs on the Green

Research assistance by B. Wellings